Columbia

Text and Photographs by Paul Clayton

Late September. What better time could there be for sailing? The brutal hot days of summer are over, the freezing rains of winter are yet to come. Of course, there are the equinoctal storms. While meteorologists and statisticians deny their existence, any old sailor will tell you to watch out around the equinox.

I drove down to Edenton on the fall equinox with a laundry list of boat jobs, and a compelling desire to get out and sail. I left Winston-Salem in cold, blustery, stormy conditions and arrived in Edenton to find warmth and gentle showers. Three days later the front caught up, and we got a couple of hours of violent storms and dropping temperatures as it moved east, pulling in cool, dry Canadian air in its wake.

Before I could go off sailing, I had work to do. I started the afternoon of the day I drove down, seizing steel rings onto to the stanchions to serve as fairleads for the furler line; continued all the day after, varnishing the seizings, testing 5/16ths line in the furler - it works, but I had to re-rig the 1/4 for the time being until I can acquire 70 feet of 5/16 - making up pendants for the tack and head of the jib; and the next day too, bending the jib, cleaning the engine compartment, fueling the engine and laying in supplies - but in the end, the boat was in shape for a short expedition. True to form, the weather was unsettled, but the warm, wet regimen gradually was displaced by the very slow moving front.

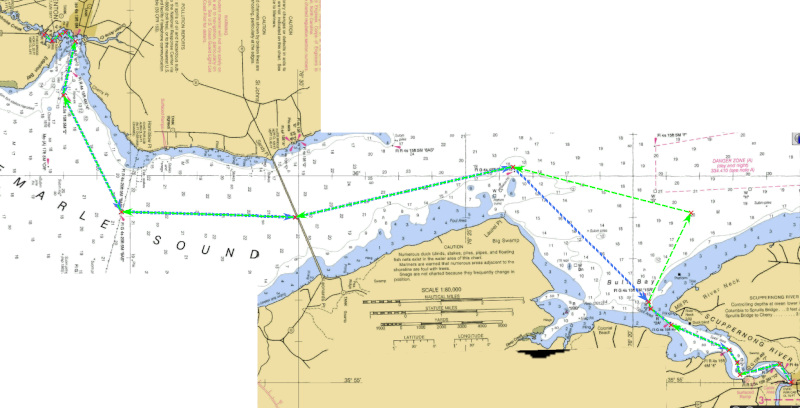

The forecast for Currituck Sound was for a small craft advisory with wind, thunderstorms and rain, expected to clear out in the afternoon, and the forecast for Edenton was north winds 5-10, blue skies. I figured I could ride along behind the front and have an easy motor-sail to Elizabeth City. If things didn't work out, I could dodge in to Columbia.

Promptly at 8:00 AM I cast off lines and backed out of my slip. I motored down Pembroke Creek, finding ground once but sliding over (worrisome, because the water was high. How would I get back in after a couple of days of north winds had dropped the level in the creek by a foot?). With the light wind dead astern, I chose to motor out the bay rather than contend with an uncontrollaby jibing main boom. Out near marker 2 I raised the main, finding that it was single-reefed, and considered shaking out the reef on the spot - but then decided to leave it in, since I was already resigned to a motor-sail for the day. With the light airs, the apparent wind would be close to dead ahead anyway, the reefed main just serving as a steadying sail. I rolled the jib out half-way, and laid a course for the power lines.

One thing people ask, and I have often wondered myself, is whether you have to go all the way out to the marked channel under the power lines, or if you can cut the corner and pass under a closer-in set of pylons. Obviously the wires are high enough. I recently heard why the authorities on the matter suggest following the marked channel. Many years ago, the railroad trestle across Albemarle Sound followed closely along the power line. When it was removed, it is possible that all the pilings were not taken out. So some of them may still be lurking below water level, just waiting to stave in the hull of a passing boat. This is the kind of thing that gives sailors nightmares, and good enough reason to follow the marked channel.

With northerly 10-knot winds, the sails were providing the motor with some help, and we made good time past the power lines and on toward the 32/37 highway bridge. I hove to for a few minutes, just to see how the boat would handle under a reefed main, and was satisfied. Even so, we made the 4.3 nm in one hour.

A couple of disconcerting things happened as we approached the bridge. I noticed the wind was veering slightly to the northeast. A dead beat down the sound to the mouth of the Pasquotank River is not my idea of fun. Plus, far ahead, past the bridge, I could see a line of white water. It looked like a distant rapid would look on a mountain river - only it was 3/4 of a mile wide.

Past the bridge, the wind started to pick up and veered even more to the east. Evidently I had caught the back edge of the front. Ahead, the sky was dark and cloudy, above and behind it was mostly blue. The seas got rougher, the wind got stronger - not the 5-10 of the forecast, more like 15-20, with higher gusts. I pushed on to the east. Clearly I couldn't go to Elizabeth City in these conditions, but if I could make it to the mouth of Bull's Bay I could turn in and sail a beam reach to the mouth of the Scuppernong River. From there it would be a sheltered run to the town dock in Columbia.

Waves crashed over the bow and ran down both side decks as the jib luffed, the main filled and the motor pushed us on. I remembered what a beating Harrison and I took aboard his Cabo Rico Stella a few years back, motor-sailing out Beaufort Inlet and down the coast, and how in our post-mortem we decided we should have backed off the engine rpm as to get a better ride in the heavy seas. I dropped the rpm to about 2000 and it made the ride a bit smoother, although periodically a comber would raise the bow high and then drop it into the following trough.

It took almost two hours to make the five miles from the bridge to marker 5AS at the mouth of the bay. We turned to starboard and began running fast on a beam reach, slaloming through the crab traps with the rail deep in the water. After a few minutes I decided this was too exciting and eased the main sheet, which got the boat more upright and didn't cost much, if any, speed.

Soon we approached the southern tip of Bull's Bay, where the Scuppernong River flows in from the east. I turned off from the wind and blanketed the jib, allowing me to roll it in. It was an ugly job, but so much better than having to crawl out on the foredeck and corral the sail to the stanchions. With the engine just off idle and the mainsail set, the boat settled down, bow to wind, for a moment as I jumped below and gave the chart a glance to refresh my memory of from several years earlier of the tricky entrance to the river. Go to green 1, then proceed directly to marker 2. Draw a mental line from 2 to 2A and then follow that line, ten feet to port, no deviations. From 2A, proceed to 3, and you are in the river, plenty of water.

With that commited to memory, it was time to drop the main. I went to the mast, set up the topping lift, and uncleated the main halyard. I had recently installed a rope clutch on the mast just above the starboard winch to allow me to use the winch for either the lift or the halyard, so I released it and the main came down with not much trouble. I engaged the clutch and went aft to corral the thrashing sail, getting it under enough control to do for the time. We had sagged down to lee, so I powered up the enging and proceeded back toward marker 1.

Looking forward, I wondered, why is there that big bight of main halyard thrashing about? Worse, what is that bitter end flying out almost horizontally from below the port spreader? I throttled down and jumped forward. My worst fears were realized. The main halyard had jerked loose from the rope brake and was now flying in the wind. It hadn't occured to me to cleat the tail down, and now the halyard was loose. Flowing out in the wind, it was far too high for me to grab. There was nothing to do but try to get the boat in the channel, to calmer water, and then maybe I could catch the halyard. Otherwise, it was going to be another trip to a boatyard to retrieve it from the masthead.

I motored in the channel, taking care to stay ten feet off the rhumb line, and once I reached the deep, broad water past marker 3, protected by land from the wind and waves, I went forward and retrieved the halyard. The wind had tied it in knots around the spreaders, mast and stays, preventing it from going to the masthead. I was just able to reach it. Believe me, I cleated it down good and tight.

Back in the cockpit, I motored on up the river. Then a thought crossed my mind. Had I cleated the topping lift? I eyed the end of the 70 pound wooden main boom directly over my head, dropped power to an idle and went to the mast. Well, I had jam-cleated it, but just to be sure, I put in a proper lock.

On the face dock at Columbia I spied a big sailboat, but all the slips were free. The captain of the sailboat came and caught a line, and later we sat down int Terry Ann's cockpit for a beer. He and his wife had been on the Columbia dock for three weeks, and were on their way to little Washington for winter quarters. They had spent most of the summer at Albemarle Plantation. They were liveaboards, and rarely sailed, but periodically motored from one location to another. They found the lifestyle suited them, and it sounds good to me.

Regarding the dockage at Columbia - there is one long face dock that would easily accomodate a 50-footer, and there are several very short slips - sized nicely for 25-footers, but a bit short for anything over 30. A judicious arrangement of springs and fenders makes a slip usable, especially since the location is very sheltered. Still, in a blow it might be wise to anchor off. There are pedestals on the dock with 30 amp service and water, and there is a pumpout station for boats that still use that barbarous technology.

I slept well Friday night, and late, finally getting up around 9:00. My plan was to spend the day in Columbia, get a few jobs done on the boat, and stay another night on the town dock. First job was to run the bilge pump. I was expecting a lot of water but the pump sucked air after only a minute. Next I checked the engine clock, and found what I already knew, we motored 6 1/2 hours on Friday. The stick showed we burned just over 3 gallons of diesel, right in line for the hours. With that done I walked to the hardware store, two blocks up the street, where I got some cup hooks and shock cord to secure items that had rolled around in the previous day's thrashing. I also got a length of hose for the icebox drain, so meltwater would go straight to the bilge instead of exiting in the engine compartment. With those jobs done, I carried my laptop the three blocks to the library to check mail and weather. No important mail, a good thing, and no threatening hurricanes, another good thing. Not that there weren't plenty of hurricanes, they were all far out in the Atlantic, what I have heard refered to as "fish storms". With jobs done, it was time for a nap, and after that, a walk with the camera.

Saturday evening. It had been a restful day, comparatively, and as the five o'clock hour struck, I really didn't feel hungry. So I carried a Sierra Nevada Torpedo IPA up into the cockpit and sat in the late afternoon sun. By the time I had finished it, my attitude had changed, and I went below, looking to scrounge dinner. in the counter behind the stove is a hatch, and below the hatch are a few provisions. Wow, lentils! And brown rice to go with it! I had my pressure cooker, so it wouldn't take long to prepare one of my favorite combinations. Into the pot they went, along with chopped onion, sliced carrot, and Andouille sausage. I seasoned it all with oregano, cumin, red pepper and cayenne. Half an hour later, dinner was served.

I read for a while, turned out the light and sank into a sound sleep, only to be wrenched back to wakefulness by an unusual movement of the bow. Then I heard voices. I jumped up and pushed open the companionway hatch, to see a group of teenagers disappearing up the dock. I glanced at my bow lines, finding all in order, and watched the kids until they vanished under the highway bridge. Back in my rack, I returned to a less sound sleep. An hour later, I felt someone give the bow pulpit a shake. I jumped up in time to see the perpetrators nearby on the dock, braced for flight. I called out, "Hey guys, don't cut me loose", and the four boys flushed like a covey of quail, running and laughing as they disappeared down the street. The one girl just sauntered along her way, not deigning to look back or show any notice. Always the same, the boys can be bad, but they are never as brave as the girls.

The forecast for Sunday was more 5-10 out of the north, backing to the northwest and maybe all the way to the west by late afternoon. Not a good forecast, but things didn't look to get any better for the next several days. In truth, the wind was already blowing a good deal more than 10 mph on the dock in Columbia, and I wondered what I would find on the sound.

As I motored down the Scuppernong River, I found reason to be pleased with my new Beta. Deaton's installed a propellor with more pitch to match the Beta's torque curve, and that allows the boat to move at lower rpms. I don't know if that is the reason, but the boat tracks very well and will hold a course with a tied tiller at low speeds, something it never would do with the Atomic 4. That let me get away from the tiller and tidy up the deck and cabin as we proceeded downriver.

The more we ran down the river, the worse the chop and wind got, and once we passed the tricky channel at the mouth, the bay looked much like it had two days earlier. Now the wind was blowing out of the north, maybe even northwest, dead on the nose. The waves building up in the sound were crashing into the shore and rebounding into the ones following. I knew things would be better out in the bay, away from shore, so I decided to wait to raise the main until things settled down. For the time being I would roll out a few feet of jib, which would steady the boat, and make off to the northeast on the port tack, as close to north as I could come without luffing the sail. With the motor running, we made decent time along the eastern shore of the bay, though 60 degrees off the right direction.

After a while I got the notion to set the mizzen. With it raised, the boat would weathercock on the stern and I might be able to get the main up. Since I rarely use the mizzen, it was well and thoroughly wrapped and tied, one less thing to do if I came down for hurricane drill. Hanging on to the mast with one hand and working with the other, it took a good ten minutes to get the sail loose and ready to raise. So it was a pleasure to turn the boat into the wind and haul on the halyard. Not so much when the sail got close to the top and jammed, refusing to go the last couple of feet. All my yanking on the luff and the halyard did nothing to get it to move, it was right and fully stuck in a partially raised position. The headboard was caught under the upper shroud bracket, and the halyard was wrapped around it so that it would not move. There was nothing to it, I just had to let it flap and bang back there for the rest of the trip.

Even so, we soon reached smoother water and I was able to go to the mast and raise the main, fortunately still reefed from the trip down. Now we had some pulling power and I was able to shut down the engine. We sailed up the sound, shaking out the reef as the wind declined and passing 5AS at about three. Shortly before then I had restarted the engine to give the sails some assistance.

We made good time under power with the sails providing a little when the wind gusted up. It was getting late in the day as we turned into Edenton Bay, and I decided to go in to the town dock and stay there for the night. That way I could get the boat straightened up and lines laid out for entry into the marina. My plan was to get back on the north side of the dock, so I had all my lines with me.

In the morning we sailed up Pembroke Creek and backed into my new slip, where Phil waited to take a line. Later I saw how I could unshackle the shroud on the mizzen and get the headboard free. All's well that ends well. A four day trip to Columbia that saw heavy weather, some sailing, a lot of motoring to put the new Beta to the test, and a nice lay-day on the waterfront of one of my favorite towns.

Text and Photographs by Paul Clayton. Posted 10/05/21.

Copyright © 2021 Paul M. Clayton